As many of my dear readers know, I am currently working on a biography of James Alexander Hamilton, son of America's first Treasury Secretary and pretty interesting guy in his own right.

|

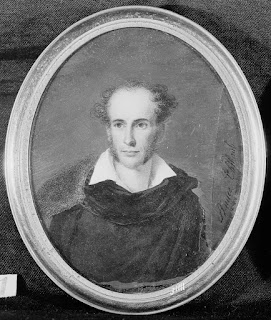

| James Alexander Hamilton |

Since he lived from 1788-1878, James observed a chaotic and important segment of US history - the entire Early Republic era, and, being the son of a Founding Father, he had loads of important people with whom he corresponded on all the vital issues of the day. One of these people was Martin Van Buren, and one of these issues was the scandal of Peggy Eaton, also known as the Petticoat Affair.

I was reading John Marszalek's book about this incident when I noticed a quote from James that did not ring true to me.

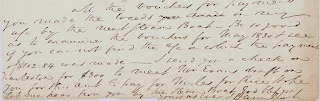

"For God knows we did not make him president to work the miracle of making Mrs E an honest woman." (The Petticoat Affair by Marszalek, p85)  |

| Excerpt of letter including quote about Mrs E LOC: Image 328 of Martin Van Buren Papers: Series 2, General Correspondence, 1787-1868; 1829; 1829, Apr. 16 - Aug. 14 | Library of Congress (loc.gov) |

While plenty of people made comments similar to this about Margaret Timberlake Eaton, who was married to Andrew Jackson's Secretary of War, John Eaton, I wasn't sure that James A Hamilton had. I have read dozens of letters written by James, and this just didn't fit. He tended to be one who didn't record a lot of negativity, though he admittedly did refer to ‘great distrust of the fitness of the two Secretaries to manage the affairs of this great Country; - a distrust which, with all my regard for the President, I cannot help indulging.’ (Reminiscences of James A Hamilton, p135)

So, I started searching for the letter to which Mr Marszalek referred in his notes as the source of this quote. 'James A Hamilton to MVB, July 16, 1829' at the Library of Congress. This took me to a 435 page file of random correspondence of Martin Van Buren dated April 16 - August 14 of 1829, so I started slowly flipping through, watching for the correct date and the handwriting that had become familiar to me as belonging to James.

This is where I encountered the first bit of evidence that my doubts were well founded. The letter dated July 16 did not look like the ones I had been painstakingly combing through for months. I looked at the end for the familiar "JAH" that James often signed off with when writing to friends.

No, this letter appeared to say "J Hamilton" with some extra letters I couldn't immediately identify.

|

| Final page of letter with Mrs E quote |

James always signed with the "A" of his middle name, whether writing out his signature or using initials. This "A" stood for "Alexander" - his father's name, and a father James was very proud to claim. I had never seen him write his name without it.

|

| Signature of James A Hamilton |

This is when I began trying to discern what other name it could be, and I remembered that another James Hamilton had sometimes come up when I was searching for "mine." I looked for letters written by South Carolina governor James Hamilton - and there it was. A matching signature with "Jr" at the end. Those were the letters I had been trying to identify, and this was the author of the letter to Martin Van Buren on July 16, 1829. I have included them both, so you can compare for yourself.

|

| Letter signed by James Hamilton Jr of South Carolina |

In case any of you have wondered how a historical writer spends their time, now you know! I have not been able to find a way to contact historian John Marszalek, and, I suppose, to most readers of his book the difference is not material, but I felt that I had solved a great mystery!