I am so excited to welcome my guest today! Amber Leigh is the author of An Honest Fame: The Story of Robert and Sally Townsend. We got connected through Culper Spy Ring research, and I was so impressed by some of her posts that I just had to invite her over. She is sharing some fun history of a popular Irish-American revolutionary for St Patrick's Day!

Welcome, Amber Leigh!

~ Samantha

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hercules Mulligan, Gentleman and Spy

Guest Post by Amber Leigh

On March 17 last year, I posted about the significance of this date for the city of Boston—not only the occasion of St. Patrick’s Day for its large Irish population, but the fact that the British evacuation of Boston took place on that same date in 1776. So, St. Patrick’s Day is Evacuation Day for Boston, as November 25 is for New York City.

But the evacuation of New York might never have taken place…were it not for a certain Irishman living there, whose contributions to the American war effort might have made the difference between defeat and victory for George Washington and his battle-weary Patriots.

This Irishman’s name was Hercules Mulligan.

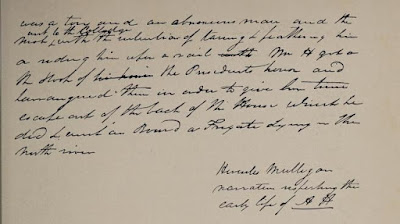

I’d have liked to post an image of him here, but I know of no surviving contemporary portraits of him. But we have samples of his handwriting, and I found this one from the electronic version of Hercules Mulligan: Confidential Correspondent of General Washington by Michael J. O’Brien, L.L.D. (New York: P. J. Kenedy & Sons, 1937):

|

| Hercules Mulligan’s handwriting. From his narrative on the early life of Alexander Hamilton. |

I happened to mention, in that article I posted a year ago today, that I initially thought of writing about Mulligan before deciding on the subject of Boston’s Evacuation Day. But the idea has stayed with me all this time, and I’m glad it did. Although we don’t know as much about Mulligan as we do about certain contemporaries of his, we know enough to judge that he was a brave, passionate, and iron-willed Patriot whose intelligence-gathering activities saved George Washington’s life…and America’s life, in the long run.

Like many Americans since his time, Mulligan’s existence began in a foreign land. He was born in Coleraine, in County Antrim in Ireland’s ancient province of Ulster, on September 25, 1740.

|

| Celtic Cross, by K. Mitch Hodge |

The Mulligans’ ancestors once bore the more stereotypically-Irish name of O’Mulligan. According to Michael J. O’Brien, one can trace them all the way back to the ninth century, as members of the bards’ class, and that was no trifling thing. In Ireland’s days of antiquity, the bards—musicians, poets, and storytellers entrusted with their people’s historical records—were the equals of noblemen and, in certain respects, of kings.

|

| The earliest-known depiction of an Irish harp, from about 1100 A.D. Courtesy of Austrasia1, Wikimedia Commons. |

But the Mulligans were not living like kings in 1740. Anyone who knows the history of Ulster is aware of the cultural, religious, and political tensions that had existed there for generations by that time, and it’s likely that the Mulligans were bristling from those tensions when they decided to emigrate. Many of the Roman Catholic natives of Ireland had converted to Anglican Christianity, so that they and their children could enjoy the same rights as the Anglo-Irish Protestants who lived in their midst. This is possibly what Mulligan’s parents (or recent ancestors) had done. And, though he remained a Protestant his entire life, he must have deeply resented the fact that so many of his countrymen had felt compelled to change their religion, just to exercise their God-given rights in their native land.

|

| Leaving Ireland, by K. Mitch Hodge |

So, six-year-old Mulligan arrived in the American colonies in 1746…in New York City, with his parents, his older brother, and his baby sister (another brother would later be born there in New York). They joined the growing Irish community there, which included several men attached to King’s College (what is now Columbia College). Mulligan’s own boyhood schoolmaster was an Irishman named James O’Brien, and he ran his school on what is now that section of William Street which is south of Wall Street.

|

| From Francis W. Maerschalck’s 1763 map of New York City. Courtesy of the Stanford University Library. |

By 1747, Mulligan’s father had attained a position as a “freeman” of the city, which meant he had the privilege of operating an independent business there in New York. The family became prosperous enough for Mulligan to attend King’s College and then, after completing his education, he worked a while for his father as a clerk.

Then, when he left to go into business on his own, he decided to open a haberdashery shop. A haberdasher, in the eighteenth century, was someone who sold cloth and “sewing notions,” like needles, thread, and scissors. But Mulligan didn’t only sell materials; he had learned to make clothing himself, and he became quite good at it. I imagine he was at least partly self-taught, and may have consulted instruction books with helpful illustrations like these (from L’Art du Tailleur by François-Alexandre-Pierre de Garsault, 1769):

He opened his first haberdashery on Smith Street (now part of William Street); around 1774, he relocated to No. 23 Queen Street, where he became a first-rate gentleman’s tailor. At his store were some of the finest materials available in the colonies, including—according to one of his newspaper advertisements—”superfine cloths of the most fashionable colours” and “silk breeches and silks of all colours.” He also employed a staff of under-tailors, which increased the speed at which his customers’ orders could be completed.

Unfortunately, none of Mulligan’s handiwork has survived to the present day, at least not any that we know of. But the British-made silk suit below, in a “most fashionable” shade of blue, dates back to as early as 1774, and it may resemble at least some of the work he and his under-tailors did.

|

| Men's Silk Coat, 1774-1793. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. |

Around this same time, John Grumly, the Assistant Surrogate of New York County, passed away…but not before naming Mulligan one of the two administrators of his large estate (we know this from an announcement made in the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury on October 17, 1774). This shows how Mulligan had become a citizen of standing, if not of great wealth and prominence.

To further illustrate this point…almost exactly a year before that—on October 27, 1773—Mulligan married Elizabeth Sanders (also written as Saunders), whose uncle, Charles Saunders, was an admiral in the Royal Navy:

|

| Admiral Charles Saunders, by Richard Brompton. Public domain. Courtesy of Dalibri, Wikimedia Commons. |

This meant, of course, that Mulligan’s in-laws were at least somewhat Loyalist, but they apparently didn’t disown Elizabeth for marrying a fiery Patriot like himself. In fact, Elizabeth’s sister later married into the aristocratic Livingston family, most of whom were Patriots before and during the Revolutionary War (Philip Livingston, for example, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence). This situation reflects the overall state of affairs in colonial America during the years leading up to the Boston Tea Party. Many Patriots and Loyalists, often finding themselves within the same family, struggled to keep things civil between them. I get the sense that Mulligan himself valued cooperation and did his best to interact politely with his opponents, whether he found them amongst his in-laws, colleagues, or customers.

But this grew more difficult as time passed and the worsening state of affairs increasingly polarized the two sides. Tensions really began to boil over in 1765, due to the controversial Stamp Act, and it is here we first find evidence of Mulligan’s patriotic activism.

Below is a satirical illustration from a 1768 British newspaper, personifying America as a woman “dismembered” by the harsh measures of the Stamp Act:

|

| The Colonies Reduced, from The Political Register, 1768 Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. |

He became a member of the Sons of Liberty, an organization that formed throughout the colonies in response to the Stamp Act. And as a Son of Liberty for New York, one of the first things he did was to help circulate copies in the city of The Constitutional Courant, an anti-Stamp Act newspaper printed in New Jersey. The Loyalist authorities in New York City forbade it, but Mulligan and his comrades found the means to sneak it in, anyway. When Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, the Sons of Liberty held a celebration each year on or near the anniversary of the repeal. An account from the March 25, 1771 issue of the Mercury described “an elegant entertainment” on the night of March 17, held by “the principal Inhabitants of the City, Friends to Liberty and Trade.” And in one of the many toasts they drank that night, they said, “Prosperity to Ireland and the Worthy Sons and Daughters of Saint Patrick.” Indeed, since this celebration coincided with the St. Patrick’s Day festivities, the Mercury reported that “Messages of Civil Compliment were exchanged by [the Sons of Liberty] and the Friendly Brothers of Saint Patrick who dined at the Queen’s Head Tavern.”

The Queen’s Head Tavern, by the way, was the former name of Fraunces Tavern, which still stands in downtown Manhattan:

|

| Fraunces Tavern |

We can be pretty certain, I think, that Mulligan was present at this “elegant entertainment,” as a representative of both the organizations who exchanged “Messages of Civil Compliment” that evening.

It is also almost certain he was present at the Battle of Golden Hill, a little more than a year before this. Many consider this incident to be the first bloodshed of the American Revolution, since at least one participant later died of his wounds and it took place well over a month before the Boston Massacre. The Battle of Golden Hill broke out because of increasing hostility between New Yorkers and the British regiments who were staying at the city barracks. Certain men among the British kept on tearing down the liberty poles, and of course Sons of Liberty like Mulligan saw that as a sign of aggression, and an affront to their freedom of speech.

Did Mulligan’s own anger ever boil over into the use of physical force? Possibly it did, although even at this point I think he still had some faith in the use of diplomacy, or at least in civilized debate. I say so because of the close friendship he formed, soon after this, with the young Alexander Hamilton.

|

| Alexander Hamilton by Thomas Hamilton Crawford. Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. |

Mulligan’s older brother, Hugh, was a New York partner at the importing firm of Kortwright & Company, at whose office (on the Caribbean island of St. Croix) Hamilton worked as a secretary. Hamilton’s employers at St. Croix, impressed by his precocity and intelligence, sponsored his journey to North America so he could get a formal education. He arrived in New York City in late 1772, with a letter of introduction to Kortwright & Company’s local partners. Through Hugh Mulligan, Hamilton met Hercules, and while he attended King’s College, Hamilton boarded with the Mulligan family and became a great favorite of them all. He dazzled them with his cleverness, but they dazzled him, too…in a different way. More specifically, he learned a great deal from Hercules Mulligan about the true state of affairs in the Thirteen Colonies.

|

| King's College, 1770. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Historian James Renwick said Hamilton initially “showed predilections toward England and his sympathies were all with England,” even to the point of claiming he would fight for the British if the colonial conflict erupted into a full-on war. So one has to wonder what exactly Mulligan said to convert this young man with “strong aristocratic prejudices” into one of the most effective advocates the colonists had in their favor. Whatever arguments he made, he must have presented them clearly and rationally, or else he might never have won over a mind like Hamilton’s.

I gather that Hamilton came to view Mulligan as a mentor of sorts, or even as an elder-brother figure. In 1774, Hamilton took up his pen to write A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress, after the First Continental Congress decided to ban all British imports. He wrote this in response to the anonymously-written, anti-Congress pamphlets of the Loyalist clergyman, Samuel Seabury (he wrote under the pseudonym “A Westchester Farmer”).

|

| Samuel Seabury, by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

They engaged each other in a print-war of sorts, from which Hamilton emerged as the clear winner in his final rebuttal, The Farmer Refuted. I imagine Mulligan was immensely proud of how this eighteen-year-old prodigy defended the Patriot cause with all the incisive brilliance of a seasoned lawyer. He must have been proud of his own role in it, as well, and not only in a general sense. Hamilton read the manuscript to Mulligan while it was still in the works, so Mulligan might have made a few suggestions here and there that Hamilton added to his final draft.

Shortly before the ban went into effect, Mulligan became a member of the first “Committee of Observation” for New York City, whose job it was to make sure the locals were implying with the directives of the Congress. He was among six men in a subcommittee chosen to carry out this committee’s orders. In the spring of 1775, the Patriots of New York formed the Committee of One Hundred to take over the government of the city in response to “the present alarming crisis” that had just taken place up at Lexington and Concord. Mulligan was among these hundred men, and he also ended up in the Committee of Correspondence for New York later in the year. Perhaps the most thrilling moment of the year for him was on the night of August 23, 1775, after the H.M.S. Asia, a Royal Navy warship, appeared in the harbor. Fearing that the crew of the Asia might swarm the Battery and take its cannons, a group of volunteers—with Mulligan and Hamilton among them—helped to haul the cannons away as the Asia began to fire on the city.

Of course, the sight of the Asia was nothing compared to the enormous enemy fleet that appeared in the harbor nearly a year later, shortly before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. By that time, thousands of people had fled New York, knowing the fleet was on its way. But Mulligan, because of his duties as a member of the revolutionary government, remained until almost the very end. He was among those who—on July 9, 1776—rushed to Bowling Green and “laid prostrate in the dust” the mounted statue of George III that had stood there for years.

|

| Pulling Down the Statue of King George III, by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel, 1859. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

He was present in the city on August 27, when the devastating Battle of Long Island occurred, and the American army was forced to retreat back onto Manhattan. He was still there on September 15, when the British landed at Kip’s Bay and began to chase the Americans across the island. Finally, Mulligan decided to leave the city, taking his wife and children with him.

But he didn’t make it in time. The Loyalists, now in a position to take revenge, had formed patrols and militia companies and one of these caught the Mulligans as they tried to flee. They took Mulligan to the Provost Prison, but they released him at some point in October because his wife’s Royal Navy uncle, Admiral Charles Saunders, put in a good word for him.

In return for such a favor, Admiral Saunders expected his nephew-in-law to be on constant good behavior, which he was…on the outside, anyway. On or near November 20, Mulligan managed to track down Alexander Hamilton, who, as an artillery captain, had accompanied the Continental Army on its retreat into New Jersey. We know this because Mulligan said so himself, in a memoir he wrote later in life at the request of Hamilton’s son. He did not say how he managed to get there undetected, but it was almost certainly at this point when he agreed to stay in New York to gather intelligence for the Continentals, and that Hamilton recommended him to Washington as an ideal man for the job.

It was, like many of Hamilton’s ideas, brilliant. With Admiral Saunders vouching for him, wealthy British officers making him their tailor of choice, and an elder brother engaged in trade with the royal forces, Mulligan had many opportunities to uncover valuable secrets. And he did, on numerous occasions. We can’t know for certain how regularly he gathered information, whether he had a particular means of recording it, or how often he sent it out, but we do know of isolated instances when he heard something very specific, which later ended up having crucial consequences (in a good way, of course) for Washington and his men.

Perhaps Mulligan’s first round-up of intelligence took place via his acquaintance with a fellow Son of Liberty, the financier Haym Salomon.

|

| Haym Salomon, from bust. From the National Archives at College Park. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Cato’s involvement in Mulligan’s spy career was key; he was often, if not always, the means by which Mulligan sent his intelligence to the Continental camp. Because Cato was an enslaved black man, the British did not suspect him of anything nefarious. And since Mulligan’s customers included officers stationed near American lines in New Jersey, they only thought it natural that he should carry letters and packages across the Hudson. In this manner, Cato was able to slip intelligence across the lines. He possible began to do this as early as April of 1777.

Like Mulligan, Salomon found himself trapped in enemy-occupied New York, but the latter had been imprisoned alongside Nathan Hale and had narrowly escaped execution himself. But because he spoke fluent German, the British pardoned him in exchange for his services as a translator between them and their Hessian allies. Since Hessian officers also needed special tailoring services, Mulligan targeted some advertisements toward them and sent them to Salomon, via his manservant Cato, to be translated into German. Later, Cato would return with the requested translations, which also happened to conceal intelligence from Salomon about any joint movements the British and Hessians were planning.

And what might he have been smuggling around that date? Possibly something to do with Sir William Howe’s plans to capture Philadelphia, the “rebel” capital. He did succeed in capturing it later that year, but only after Washington’s men gave him some stiff resistance…some of which may have had to do with timely tidbits delivered from Mulligan via Cato.

Mulligan, I suspect, might have enjoyed plying his customers for information. He bowed and scraped, as they expected him to, and he served them wine—or whatever alcoholic beverage they preferred—which induced a relaxed attitude and loose lips.

|

| Photo by Han-eck/Shutterstock |

And, instead of having his under-tailors measure these important fellows, Mulligan took their measurements himself, perhaps flattering them on their superior taste in fashion…gradually leading them to chitchat on more significant matters.

Naturally, after the British garrison left New York to occupy Philadelphia, he had fewer opportunities to do this. But things picked up again quickly enough when they returned in June of 1778. Soon afterwards, a British spy, noticing Cato returning from a mysterious journey across the East River, reported Cato to William Cunningham, the infamously-cruel Provost Marshal of the New York prisons. Cunningham had hated Mulligan since the latter’s days as a Son of Liberty, and he hoped to force Cato to reveal something incriminating about his master. He treated Cato brutally, having him beaten, but Cato remained silent as the grave, eventually obligating Cunningham to let him go. Cato’s act of self-sacrificing faithfulness was something Mulligan never forgot, as we shall see later.

It was in late summer of this year when Abraham Woodhull (Samuel Culper, Senior) first began to spy for Washington under supervision of his old friend, Major Benjamin Tallmadge. On October 31, Woodhull reported to Tallmadge that he’d acquired assistance from “a faithfull freind [sic] and one of the first characters in the City,” with whom he met in or near the city every week.

Below is the quoted excerpt from this letter:

|

| Excerpt from A Woodhull's Culper Letter, 31 Oct 1778. Courtesy of the George Washington Papers, Library of Congress. |

While there has been some disagreement among historians about whom Woodhull was referring to, it’s not unreasonable to think it might have been Hercules Mulligan.

But if it was Mulligan, then one wonders how the two were introduced. It could have been via Robert Townsend (Samuel Culper, Junior), even though Townsend didn’t become a spy himself until the following summer. And Mulligan, perhaps, continued as a lone operative even while he occasionally shared tips with Woodhull (and later with Robert Townsend, too). In January of 1779, for instance, he sent Cato out to New Jersey to warn Washington that a plot was underfoot to capture him. He learned this when an officer, late one night, came to Mulligan to order a new watch coat, saying he needed it by morning. When Mulligan inquired about the rush, the officer replied that the British were going to ambush Washington, and that before another full day passed, they’d have “the rebel general” in their hands. But, thanks to Mulligan’s timely warning, Washington changed his plans and avoided the ambush.

Then, in July of 1780, the British learned that a French fleet was going to rendezvous with Washington in Rhode Island. The British knew certain details, like the size of the fleet, and they planned to send up a fleet of their own to surprise the French before they could disembark. Mulligan and Townsend found out about this, although it’s not clear whether each one discovered it on his own, or whether Mulligan discovered it first and then passed it on to Townsend. But each one separately conveyed the information to Washington—Townsend by the Culper courier, and Mulligan by Cato. Between them, though, they ended up foiling the British plan to ambush the French.

In October, after the execution of John André, Benedict Arnold fled to New York City, revealing himself as a turncoat. Desperate to ingratiate himself with Sir Henry Clinton, he began to round up people there in the city whom he suspected of being spies. It was too much to hope that Mulligan would escape detection this time, and he didn’t: On or around the 20th of October, he was arrested and taken to the Bridewell Prison on the northern half of Broadway.

|

| Old Bridewell Prison, New York City, by H.R. Robinson. Courtesy of Wellcome Images, via Wikimedia Commons. |

The Bridewell was infamous for having no glass in the windowpanes to keep out the elements, but Mulligan made use of this defect—he slipped from the window during the changing of the guard, and dropped into the prison yard. Then he tried to climb over the wall, but was spotted by the new guard coming to relieve the old one. So they took him to the Provost Prison, and afterwards he encountered Benedict Arnold himself. William Cunningham had apparently blabbed his suspicions to Arnold, but then Arnold, having been in the Continental camp, might have already had an inkling about who Mulligan was.

Things looked pretty hopeless for Mulligan at that point, but some might say he had the luck of the Irish on his side.

|

| Shamrock by Dustin Humes |

Arnold and Cunningham couldn’t dredge up any solid evidence against him, and eventually had to send him home!

But this experience was enough to knock him down a peg or two in the eyes of the British, who referred to him as “the rebel Mulligan.” It appears his tailoring business took a hit, as well; he sank into debt and wasn’t able to work as a tailor again until 1786. But he didn’t stop collecting intelligence, at least not when he learned of yet another threat to Washington’s life in February of 1781. Hugh Mulligan, upon receiving a rush order for a large load of provisions, discovered that about three hundred men were going north to capture Washington on his way to confer with the French General Rochambeau. Hugh ran to inform Hercules, who then sent Cato out to the Continental camp. This was the second time Mulligan saved Washington’s life.

And so Washington, after the British evacuated New York on November 25, 1783, wanted to show his gratitude to Mulligan in person. Right after the British left, Washington went to Mulligan’s home in Queen Street and had breakfast with him!

The end of the war brought a return of Mulligan’s old social zeal, and newspapers from the time show how public-spirited he was. He became a vestryman at Trinity Church, where he helped to establish a formal church choir and a school for teaching church music. He was a member of the Marine Society of the City of New York, an organization “for the relief of distressed shipmasters or their widows and children.” In 1786, he joined the anti-slavery New-York Manumission Society, founded by his old pal, Alexander Hamilton, and became a decided abolitionist. He ended up freeing Cato, who I believe—though I have no definite proof of it—might have established himself in business as the owner of an oyster cellar.

During Mulligan’s remaining years, life was good to him. After Washington became President in 1789, he made Mulligan his official clothier. Of course, that was easier at first, when New York City was the national capital. But even after relocating the capital to Philadelphia, Mulligan still received commissions from his grateful president. Below is a note to Mulligan from Washington’s secretary, Colonel Tobias Lear, placing an order on Washington’s behalf:

|

| Letter from Tobias Lear to Hercules Mulligan. From the George Washington Papers. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

In fact, we can see in Colonel Lear’s transaction records that Washington ordered a formal suit from Mulligan (made from fourteen-and-a-half yards of black velvet), described later as “resplendent.” Perhaps that suit looked something like this one, from the world-famous Landsdowne portrait by Gilbert Stuart:

|

| Gilbert Stuart’s Landsdowne portrait of George Washington, 1796. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. |

Mulligan continued to work as a tailor until the age of eighty, when he finally retired. He died, eighty-four years old, at the Cedar Street home of his son, the lawyer John W. Mulligan, on March 4, 1825. He is buried under the Whalie family vault (the family his sister married into), at Trinity Churchyard in Manhattan, not far from where Alexander Hamilton lies beside his wife, Eliza Schuyler Hamilton.

Mulligan’s activities as a Revolutionary War spy became known long before those of the Culpers; unlike them, he wasn’t afraid of others knowing about what he did. So he appears in scholarly works on the subject written before 1930, when Morton Pennypacker discovered the Culpers’ identities. Of course, he can also be found in much more recent works, and not only in scholarly ones…his character appeared in the fourth season of the AMC series Turn: Washington Spies, and in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash-hit Broadway musical, Hamilton.

I will end this post by making a virtual toast to Mulligan’s memory in the form of a link to the Hercules Mulligan Company, maker of a rum and rye blend flavored with ginger and bitters.

Notice the thimble and shears on the label? They called their company after our subject, and refer to him on their site as “Agent Double-O-Needle,” which I find amusing. I think Mulligan would have been amused, too.

Connect with Amber Leigh

Amber Leigh has a B.A. in history, and an M.A. in Documentary Film and History from Syracuse University. Her past writing projects include a ghostwritten three-part series and a contemporary novella, Thy Neighbor as Thyself. An Honest Fame: The Story of Robert and Sally Townsend is her debut novel. Visit www.amberleighauthor.com to learn more.

You can also connect with Amber Leigh on Facebook, Goodreads, and Instagram.

An Honest Fame: The Story of Robert and Sally Townsend

Witness the birth of our country through the lives of two unlikely heroes...

Robert and Sally Townsend, children of a prominent Long Island Quaker, have simple goals. Robert wishes for an independent life as a merchant in New York City, and Sally hopes to become the accomplished young lady she's long striven to be. But escalating tensions between the colonies and Britain interrupt their plans, upending life as they have always known it.

They see their father, outnumbered and opposed by his Loyalist neighbors, struggle for the Patriot cause as war looms ever nearer. Then the British arrive, invading and conquering New York City, Long Island...and the Townsend home.

After returning to work in a vanquished city, Robert fights the enemy with the only weapon at his disposal—deception. Compromising his Quaker honesty, he joins a ring of spies in the employ of George Washington. He tries his best to continue life as usual, ferreting out secrets while living in constant fear of discovery.

Sally, meanwhile, conceals her anger with smiles as she and her family cater to their enemies’ whims. Then comes a day when her smiles are no longer forced, and her enemies become her friends. When she loses her heart to a British officer, she wonders whether she can be loyal to him and to her country at the same time.

An Honest Fame: The Story of Robert and Sally Townsend is a retelling, both epic and intimate, of the tale of these two real-life siblings. Their coming-of-age takes place during a time of immense upheaval, during which they influence the course of events in ways they never expected.

Was Hercules his real name or a code name?

ReplyDeleteThat was his real name. He was born to be cool.

DeleteHopefully his dad was better than Zeus!

Delete